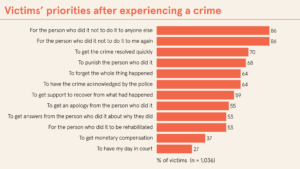

‘I wanted her caught. I didn’t want to ruin her life, but I didn’t want her to walk away.” This victim of abuse and assault speaks for many. Most victims of crime don’t want to put their assailants in prison and throw away the key. When Transform Justice asked over a thousand victims of crime what was important to them, their top priority was for the crime not to happen again to them or anyone else. They cared as much about preventing other people being victims as themselves.

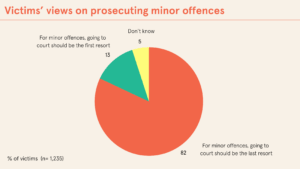

Most victims also wanted the person who harmed them to be punished but the punishment had to fit the crime. This usually didn’t mean prison or even court. Victims felt too much court time was wasted on minor offences and that court would be stressful: “Why go to court, why have to stand up and give a witness statement? Why go through that? None of that is nice for either side.”

Increasing delays in the magistrates’ courts means it now takes on average 182 days from a crime happening to the final hearing. Most of those convicted in the magistrates’ courts must pay a fine, which is neither tailored nor rehabilitative. No wonder many victims welcome another way.

If the suspect admits to it, police can deal with a wide range of crimes using an out-of-court resolution, a low-level criminal sanction. This can be a win-win for victims. They get their crime resolved — which most crime isn’t — they get a say in how it’s dealt with, and it’s quick.

We interviewed a woman, ‘Sarah’, who was bitten by a dog when she put her hand through a letterbox to deliver leaflets. The bite was serious and required hospital treatment, and she reported it to the police.

“I didn’t want to take anyone to court, I didn’t want to go through that, or put anybody else through that. My main concern was safety for other people. Taking the man to court wasn’t going to resolve a safety issue.”

Sarah and the police officer agreed on a community resolution that required the owner of the dog to get a metal box around the letterbox to catch letters and protect people’s hands. The officer gave the owner a week to abide by the resolution, which he did. The crime was resolved in less than two weeks.

“I’m quite happy with the whole thing. You know, if something like that happens again, I wouldn’t hesitate to go through the same process because I just think it worked.”

While victims whose cases go to court have little influence over the outcome, police using out-of-court resolutions must ask victims what they want. Victims can request financial compensation, an apology, or that the person does something rehabilitative like an anger management course.

The government is waking up to the need to resolve more crime but without clogging up the courts with petty offences. Many have suggested to Sir Brian Leveson (who is about to publish a review of the criminal courts) that a large proportion of the offences dealt with in the magistrates’ courts could be more effectively dealt with outside. Our research suggests victims would agree.

Read our report into victims’ experiences of out of court resolutions, and sign up for our webinar on Monday 14th July to discuss the findings.